Just in case the picture of a man’s final moment at Pompeii has inspired people this morning, Ancient Greek for (male) masturbation:

Aristophanes, Peace 290-292

“Now comes the time of for Datis’ song

The one he sang once at midday as he masturbated

“How I am pleased and I enjoy this and I am finding delight!”

ΤΡ. Νῦν, τοῦτ’ ἐκεῖν’, ἥκει τὸ Δάτιδος μέλος.

ὃ δεφόμενός ποτ’ ᾖδε τῆς μεσημβρίας·

«῾Ως ἥδομαι καὶ χαίρομαι κεὐφραίνομαι.»

The small LSJ defines δέφω as “to soften by working by the hand, to make supple, to tan hides.” The 1902 LSJ uses Latin to explain: “sensu obscoeno, v. Lat. Masturbari.”

The Suda (delta 297) cuts to the chase on this one with “dephein: grabbing someone by the genitals. Also, “rubbing” (Dephomenos) instead of “flogging your genitals.” (Δέφειν: τὸ τοῦ αἰδοίου τινὰ ἅπτεσθαι. καὶ Δεφόμενος, ἀντὶ τοῦ ἀποδέρων τὸ αἰδοῖον). So, the active vs. middle voice is an important distinction (echoing something I have emphasized in teaching Greek: active voice is something you do to someone else, middle is what you do to yourself…).

Here’s a nice passage that shows the difference in active and passive voice:

Artemidorus, Dream Interpretation 1.78: 74-80

“I know of a certain slave who dreamed that he was masturbating his master—and he then became the teacher and nurse of his children. For he was holding his master’s genitals in his hands which was a symbol of his children. And again, I know of another who dreamed he was being jerked off by his master, and, later he was bound to a pillar and then he received many blows…”

οἶδα δέ τινα δοῦλον, ὃς ἔδοξε τὸν δεσπότην αὐτοῦ δέφειν, καὶ ἐγένετο τῶν παίδων αὐτοῦ παιδαγωγὸς καὶ τροφός· ἔσχε γὰρ ἐν ταῖς χερσὶ τὸ τοῦ δεσπότου αἰδοῖον ὂν τῶν ἐκείνου τέκνων σημαντικόν. καὶ πάλιν αὖ οἶδά <τινα> ὃς ἔδοξεν ὑπὸ τοῦ δεσπότου δέφεσθαι, καὶ προσδεθεὶς κίονι πολλὰς ἔλαβε πληγάς….

Most of the extant uses of this verb appear in comedy. And, not surprisingly, this means Aristophanes:

Aristophanes, Knights 23-24

ΟΙ. Β′ Πάνυ καλῶς.

῞Ωσπερ δεφόμενός νυν ἀτρέμα πρῶτον λέγε

τὸ μολωμεν, εἶτα δ’ αὐτο, κᾆτ’ ἐπάγων πυκνόν.

“Excellent.

Just as if you were masturbating, say it first now gently

“let us hurry” and then again pushing on, quickly.”

[Here’s a link to the whole play. Soon, one of the interlocutors stops “because the skin is irritated by masturbation.” (῾Οτιὴ τὸ δέρμα δεφομένων ἀπέρχεται, 29)]

The verb is not common, to say the least, so later commentators found it necessary to gloss it and explain Aristophanes’ joke. Through the explanations of the joke, it immediately becomes less funny, and the language used in the commentaries.

Scholia in Knights:

[1] “ ‘Just like dephomenos’: instead of “flogging your genitals” (apodérôn to aidoion). For, when men touch their genitals they don’t complete as they began, but they move more eagerly towards the secretion of semen. This plays on that, he means start small at first but then go continuously.

[2]‘dephomenos’: “having intercourse’. Flogging genitals.

[3]‘dephomenos’: They mean handling the penis. For, when men take hold of their penises they don’t move towards ejaculation the way they began, but more eagerly over time, as they are inflamed by the continuity of movement.”

ὥσπερ δεφόμενος: ἀντὶ τοῦ ἀποδέρων τὸ αἰδοῖον. οἱ γὰρ ἁπτόμενοι τῶν αἰδοίων οὐχ ὡς ἤρξαντο, ἀλλὰ σπουδαιότερον κινοῦσι πρὸς τῇ τῆς γονῆς ἐκκρίσει. τοῦτο οὖν λέγει, ὅτι πρῶτον κατὰ μικρόν, εἶτα συνεχῶς λέγε. RVEΓ2M

δεφόμενος] ξυνουσιάζων, ἀποδέρων τὸ αἰδοῖον. M

δεφόμενος] ἤγουν τοῦ μορίου ἁπτόμενος. οἱ γὰρ ἁπτόμενοι τοῦ μορίου

πρὸς ἔκκρισιν τῆς γονῆς οὐχ ὡς ἤρξαντο κινοῦσιν ἀλλὰ σπουδαιότερον, ἐκπυρούμενοι τῇ συνεχείᾳ τῆς κινήσεως. VatLh

Aristophanes, Ecclesiazusae, 705–709

“It is decreed that the ugly and the wretched

Get to fuck first.

Take your pleasure on the porch in the meantime

Handling your fig-leaves in the courtyard”

τοῖς γὰρ σιμοῖς καὶ τοῖς αἰσχροῖς

ἐψήφισται προτέροις βινεῖν,

ὑμᾶς δὲ τέως θρῖα λαβόντας

διφόρου συκῆς

ἐν τοῖς προθύροισι δέφεσθαι.

The Suda interprets this passage as meaning that someone is masturbating with a fig leaf. Henderson ( The Maculate Muse. New Haven 1975) explains that the “fig-leaves” are the foreskin and the “courtyard” means outside of a vagina.

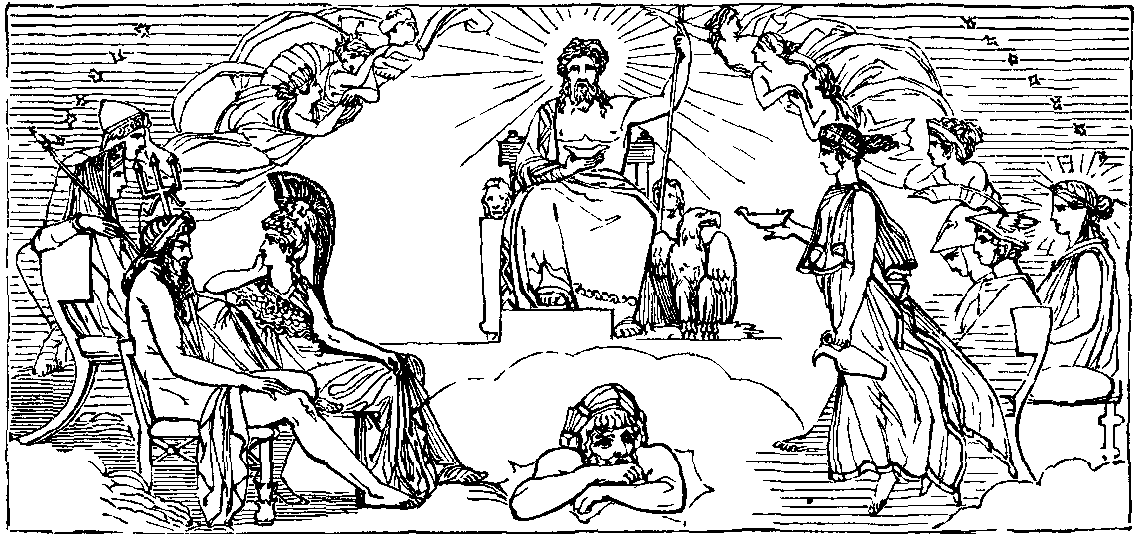

![Image result for ancient Greek Masturbating vase]()

And just in case one might worry about moral dimensions of masturbation, ancient philosophers have already tackled the question:

From Sextus Empiricus Pyrrhonian Hypotyposes, 3.206-207

“Similarly, this seems shameful to one of the sages but not to another. For us it is wrong to marry your own mother or sister. But the Persians, especially those of them who seem to pursue wisdom, the Magi, marry their mothers just as the Egyptians marry their sisters. The poet also says: “Zeus addressed Hera, his wife and sister…”

Zeno of Citium even says that it is not strange to rub your mother’s genitals with your own, just as no one would claim it is wrong to rub any other part of her body with your hand. Chrysippus approves in his Republic of a father getting children from his daughter, a mother from her son, and a brother from his sister. Plato insisted generally that wives should be held in common. Zeno also does not disapprove of masturbation, which is shameful in our culture. We have also learned that others practice this wicked habit as if it were a good thing.”

οὕτω καὶ τῶν σοφῶν ᾧ μὲν οὐκ αἰσχρόν, ᾧ δὲ αἰσχρὸν ἐδόκει τοῦτο εἶναι. ἄθεσμον τέ ἐστι παρ’ ἡμῖν μητέρα ἢ ἀδελφὴν ἰδίαν γαμεῖν· Πέρσαι δέ, καὶ μάλιστα αὐτῶν οἱ σοφίαν ἀσκεῖν δοκοῦντες, οἱ Μάγοι, γαμοῦσι τὰς μητέρας, καὶ Αἰγύπτιοι τὰς ἀδελφὰς ἄγονται πρὸς γάμον, καὶ ὡς ὁ ποιητής φησιν,

Ζεὺς ῞Ηρην προσέειπε κασιγνήτην ἄλοχόν τε.

ἀλλὰ καὶ ὁ Κιτιεὺς Ζήνων φησὶ μὴ ἄτοπον εἶναι τὸ μόριον τῆς μητρὸς τῷ ἑαυτοῦ μορίῳ τρῖψαι, καθάπερ οὐδὲ ἄλλο τι μέρος τοῦ σώματος αὐτῆς τῇ χειρὶ τρῖψαι φαῦλον ἂν εἴποι τις εἶναι. καὶ ὁ Χρύσιππος δὲ ἐν τῇ πολιτείᾳ δογματίζει τόν τε πατέρα ἐκ τῆς θυγατρὸς παιδοποιεῖσθαι καὶ τὴν μητέρα ἐκ τοῦ παιδὸς καὶ τὸν ἀδελφὸν ἐκ τῆς ἀδελφῆς. Πλάτων δὲ καὶ καθολικώτερον κοινὰς εἶναι τὰς γυναῖκας δεῖν ἀπεφήνατο. τό τε αἰσχρουργεῖν ἐπάρατον ὂν παρ’ ἡμῖν ὁ Ζήνων οὐκ ἀποδοκιμάζει· καὶ ἄλλους δὲ ὡς ἀγαθῷ τινι τούτῳ χρῆσθαι τῷ κακῷ πυνθανόμεθα.

![]()

![]()

♀️

♀️